In the early 1800’s, as settlers moved westward across America, a dispute arose between the Americans and the British over ownership of the Oregon Country, land covering much of today’s Pacific Northwest, stretching from Oregon through Washington and up into British Columbia and parts of Idaho and Wyoming. While the territory had been declared to be in joint possession of the two governments, as more and more settlers moved in, the British claimed that land ceded to them in previous treaties and through the work of the Hudson’s Bay Company was being encroached upon.

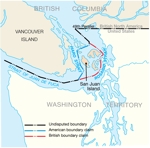

After a few years of slightly strained tensions, in 1846 the Oregon Treaty peacefully resolved the dispute, setting the 49th parallel as the upper boundary of the United States. As the 49th parallel cuts directly through Vancouver Island when extended westward, it was determined that the boundary line would extend “to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island; and thence southerly through the middle of the said channel, and of Fuca’s straits to the Pacific Ocean.” Unfortunately, that wording proved to be unclear enough to set the stage for another conflict.

The difficulty lay in that there were two straits running southward through the islands — Haro Strait and Rosario Strait. As each country wanted the most advantageous boundary line, each claimed that the boundary ran through whichever strait would grant them the islands, with the British running the boundary line through Rosario Strait and the Americans, Haro Strait.

Over the next few years, both the British and the Americans started utilizing San Juan Island, with each group assuming that the other group was there illegally. By 1859, the British Hudson’s Bay Company had both a salmon-curing station and a sheep ranch operating on the island, and the Americans had about eighteen settlers living there also. Tempers were short, but things didn’t come to a head until June of 1859.

On June 15 of that year, American settler Lyman Cutlar discovered a pig rutting through his garden. He shot and killed the pig — which belonged to his neighbor, an Irishman employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company. When Cutlar offered to pay for the pig, his neighbor claimed that the pig was a champion breeder and demanded $100 for the loss. Considering this high price to be unreasonable, Cutlar refused to pay. British authorities, already considering Cutlar and the rest of the settlers to be illegal squatters, threatened to arrest him. The American settlers, none to happy about these British who refused to leave their island, petitioned for U.S. military protection. On July 27th, a 66-man company of the 9th U.S. infantry, commanded by Cpt. George E. Pickett, landed on the southern tip of the island and set up camp.

The British governor of British Columbia’s Crown Colony, angered by the arrival of U.S. troops. answered by sending in his own forces — three British warships commanded by Cpt. Geoffrey Hornby — with instructions to remove Pickett from San Juan Island, but to avoid any actual hostilities if at all possible.

Over the next few months, each side continued to send in reinforcements, until by the end of August, “461 Americans, protected by 14 cannons and an earthen redoubt, were opposed by three British warships mounting 70 guns and carrying 2,140 men, including bluejackets (sailors), Royal Marines, artillerymen and sappers.”

Incidentally, the construction of the redoubt at the top of a hill in the American camp to let the cannon oversee the water approaches to the island was supervised by engineer Henry Martyn Robert. Later in his military career, Robert discovered a fascination with parliamentary procedure, and went on to author Robert’s Rules of Order.

Thankfully, throughout all of this territorial saber-rattling, saner heads prevailed, refusing to “involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig,” in the words of British Rear Admiral Robert L. Baynes. Eventually, U.S. President James Buchanan dispatched General Winfield Scott to resolve the affair. Scott was able to broker a treaty, with each country reducing their forces — a single company of U.S. troops, and a single British warship — allowing the island to continue under joint occupation until a more formal resolution could be reached.

This situation continued for the next twelve years, making the Pig War the longest single military conflict on U.S. soil — even if the only casualty was a hungry pig. Eventually, during the signing of the Treaty of Washington between Britain and the United States, Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany was asked to arbitrate in the matter of the San Juan Islands. He referred the matter to a commission, and after a year of deliberation, the commission ruled in favor of the United States on October 21st, 1872. British troops withdrew from San Juan Island within the month, and the last of the U.S. troops left by mid-1874.

Sources:

- National Park Service: The Pig War

- Todd Matthews: The Pig War of San Juan Island

- Rocky Mountain Books: Pig War on San Juan

- Discovery Inn: The famous Pig War and Other Adventures

- John Stang, Tri-City Herald: San Juan Islands overflow with adventure