I’m quite curious about iA Presenter (a new Markdown-focused presentation creation app), so I downloaded the 14-day trial.

And it is immediately driving me up the wall that in the sample/instructional presentation that loads by default, the creators are repeatedly misusing headings to create the style for their demonstration slides.

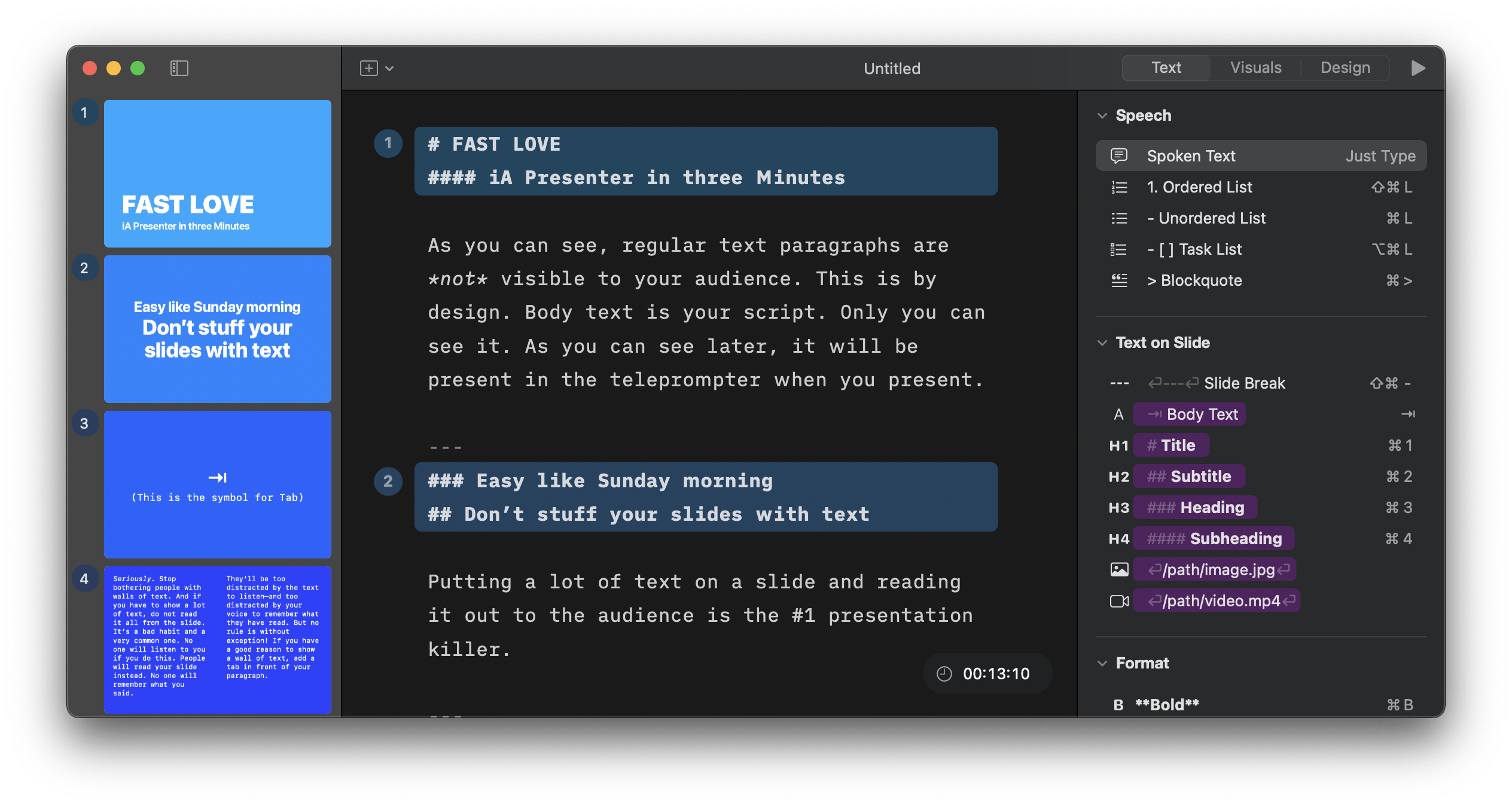

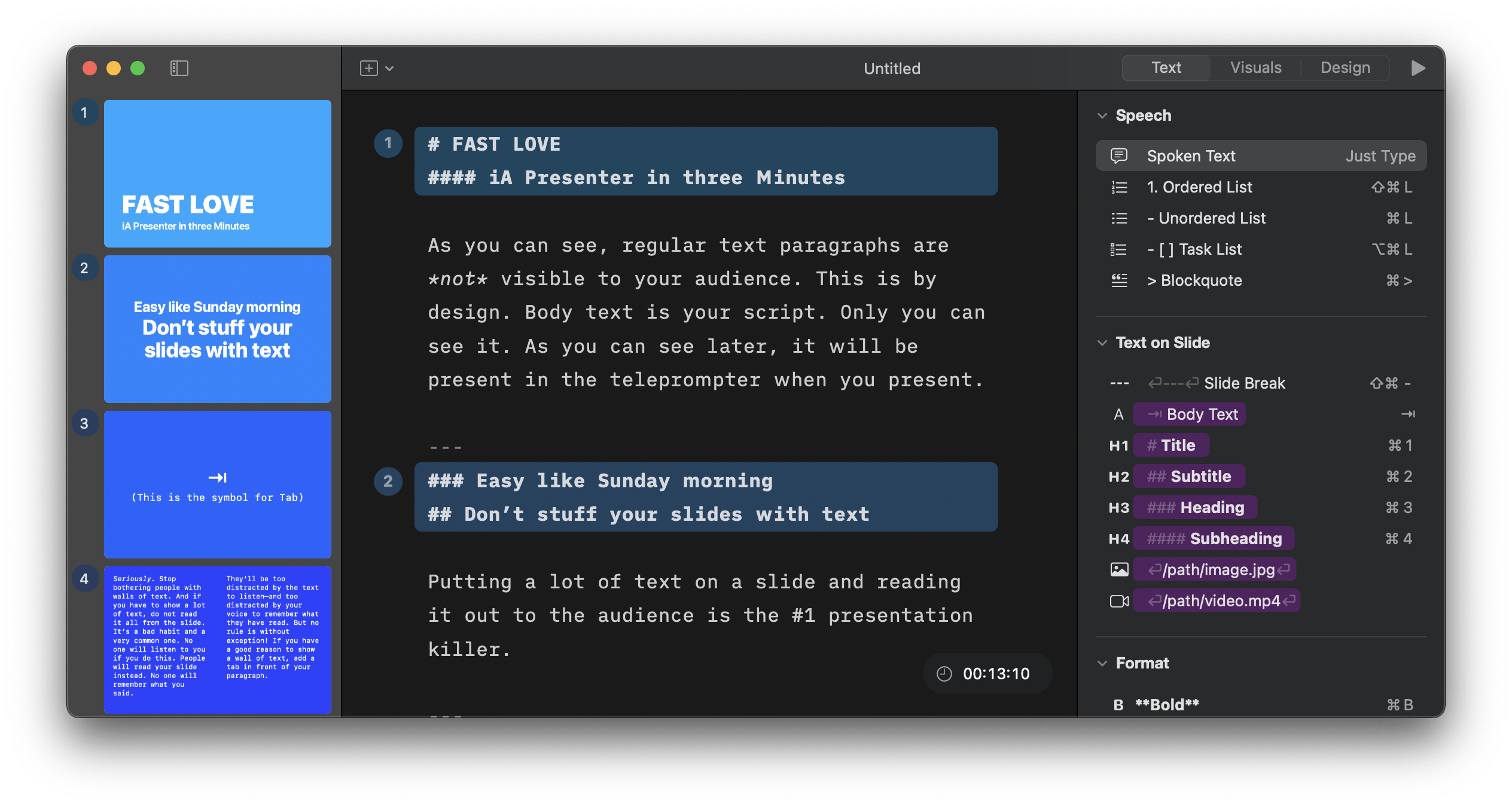

The cover slide starts with an H1 and then immediately jumps to an H4, presumably because they wanted the visual distinction between the larger text of the title and the notably smaller text of what’s being used as a subtitle. But that skips two levels of headings.

The second slide (and many other slides) starts with an H3 that is immediately followed by an H2. Consistently, slide after slide, it’s an H3 followed by an H2. Again, this appears to be done for the visual presentation, as it results in the smaller-text headline over the larger-text headline. But that means that the headings are all out of order and don’t create a consistent outline to indicate the structure of the document.

And this sort of thing continues throughout the entire demo presentation.

Not only is this generally sloppy, but it’s an accessibility issue: When headings are skipped, users of assistive technology like screen readers have to try to figure out from context whether the headings have actually been skipped, or if they’re they exist but haven’t been tagged properly, or if they’re being presented out of order. When the document outline is out of order, it makes it much more difficult to navigate through and build a coherent mental picture of the final document.

I haven’t gotten as far as looking to see how iA Presenter does with its output (Is the HTML it generates standards compliant? Are the PDFs it generates properly tagged for accessibility)? But even if it exported perfect HTML or ideally tagged PDFs, the content will have accessibility issues because the designers are prioritizing style over substance. And with this as their demo, many people using the app will likely follow their lead.

And that’s a shame. Because on first blush, it’s a gorgeous app with some extremely good advice on how to conceptualize and plan better presentations and some great templates. All criticisms aside, I’m still looking forward to experimenting with it. But the abuse of headings and lack of concern for reasonable document structure is not giving a very good first impression.

Read more