I’ve been an Affinity Photo/Designer/Publisher user since sometime before 2019 (the first mention I can find here), and have recommended them to a lot of people as a less expensive but (nearly) equivalent alternative to Adobe’s Photoshop/Illustrator/InDesign suite of apps. Last year Affinity was acquired by Canva, which did not thrill me (I’m not a fan of Canva, as accessibility has never seemed to be a high priority for them, and remediating PDFs created by Canva users is an ongoing exercise in frustration), but at the time they pledged to uphold Affinity’s pricing and quality. All we could do at that point was wait to see what happened.

A few weeks ago, Affinity closed their forums, opened a Discord server, removed the ability to purchase the current versions of the Affinity suite of apps, and started posting vague “something big is coming” posts to their social media channels and email lists. Not surprisingly, this did not go over well with much of the existing user base, and we’ve had three weeks of FUD (fear, uncertainty, and doubt), with a lot of people (including me) expecting that Canva would taking Affinity down the road of enshittification.

Yesterday was the big announcement, and…

…as it turns out, it looks to me at first blush that it doesn’t suck. The short version:

- Affinity Photo, Designer, and Publisher have been deprecated, all replaced with a single unified application called Affinity by Canva.

- The existing versions of the old Affinity suite (version 2.6.5) will continue to work, so existing users can continue to use those if they don’t want to update. In theory, these will work indefinitely; in practice, that depends on how long Canva keeps the registration servers active and when Apple releases a macOS update that breaks the apps in some way. Hopefully, neither of those things happens for quite some time (and if Canva ever does decide to retire the registration servers, I’d really hope that they’d at least be kind enough to issue a final update for the apps that removes the registration check; I don’t expect it, but it would be the best possible way to formally “end of life” support for these apps).

- Affinity by Canva is free.

- You do need to sign in with a Canva account. But you had to sign in to Affinity with Serif account, and Canva now owns Serif, so this isn’t exactly a big surprise for me.

- The upsell is that if you want to use AI features, you have to pony up for a paid Canva Pro account. Assumedly, they figure there are enough people on the AI bandwagon that this, in combination with Canva’s coffers, will be enough to subsidize the app for all the people who don’t want or need the AI features.

- “AI features” is a little vague, but it seems to cover both generative AI and machine learning tools.

-

Affinity’s new “Machine Learning Models” preferences section has four optional installs: Segmentation (“allows Photo to create precise, detailed pixel selections”), Depth Estimation (“allows Photo to build a depth map from pixel layers or placed images”), Colorization (“used to restore realistic colors from a black and white pixel layer”), and Super Resolution (“allows pixel layers to be scaled up in size without loss of quality”). Of these, Segmentation is the only one that currently is installable without a Canva Pro account; the other three options are locked. The preferences dialog does have a note that “all machine learning operations in Affinity Photo are performed ‘on-device’ — so no data leaves your device at any time”.

-

The Canva AI Integrations page on the new Affinity site indicates that available AI tools also include generative features such as automatically expanding the edges of an image and text-to-image generation (interestingly, this includes both pixel and vector objects).

-

In the FAQs at the bottom of the integrations promo page, Canva says that Affinity content is not used to train AI. “In Affinity, your content is stored locally on your device and we don’t have access to it. If you choose to upload or export content to Canva, you remain in control of whether it can be used to train AI features — you can review and update your privacy preferences any time in your Canva settings.”

- If you, like me, are not a fan of generative AI, I do recommend checking your Canva account settings and disabling everything you can (I’ve done this myself). The relevant settings are under “Personal Privacy” (I disabled everything) and “AI Personalization”.

- I actually feel like this is an acceptable approach. Since I’m no fan of generative AI, I can simply not sign up for a Canva Pro account, disable the “Canva AI” button in Affinity’s top button bar, and not worry about it; people who do want to use it can pay the money to do so. I do wish there was a clearer distinction between generative AI and on-device machine learning tools and that more of the on-device machine learning tools were available without being locked behind the paywall; that said, the one paywalled feature I’d be most likely to occasionally want to use is the Super Resolution upscaling, and I can do that in an external app on the occasional instances where I need it.

So at this point, I’m feeling mostly okay with the changes. There are still some reservations, of course.

I’m not entirely sold on the “single app” approach. Generally, a “one stop shop” approach tends to mean that a program is okay at doing a lot of things instead of being really good at doing one thing, and it would be a shame if this change meant reduced functionality. That said, Affinity has said that this was their original vision, and they’ve long had an early version of this in their existing apps, with top-bar buttons in each app that would switch you into an embedded “light” version of the other apps for specific tasks, so it does feel like a pretty natural evolution.

A lot of this does depend on how much trust you put in Canva. Of course, that goes with any customer/app/developer relationship. I have my skepticism, but I’m also going to recognize that at least right now, Canva does seem to be holding to the promises that they made when they acquired Serif/Affinity.

Time will tell how well Canva actually holds to their promises of continuing to provide a free illustration, design, and publishing app that’s powerful enough to compete with three of Adobe’s major apps. Right now, I’m landing…maybe not on “cautiously optimistic”, but at least somewhere in “cautiously hopeful”.

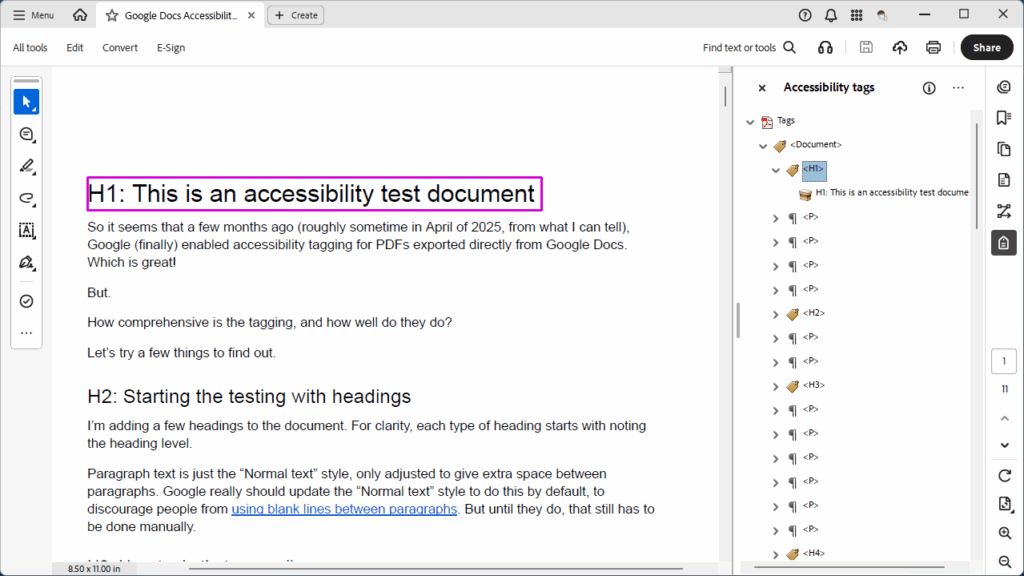

Finally, one very promising thing I’ve already found. While I haven’t done any in-depth experimenting yet, I did take a peek at the new Typography section, and styles can now define PDF export tags! The selection of available tags to choose from is currently somewhat limited (just P and H1 through H6), but the option is there. I created a quick sample document, chose the Export: PDF (digital – high quality) option, and there is a “Tagged” option that is enabled by default for this export setting (it’s also enabled by default for the PDF (digital – small size) and PDF (for export) options; the PDF (for print), PDF (press ready), PDF (flatten), PDF/X-1a:2003, PDF/X-3:2003, and PDF/X-4 options all default to having the “Tagged” option disabled).

When I exported the PDF (38 KB PDF) and checked it in Acrobat, the good news is that the heading and paragraph tags exist! The less-good news is that paragraphs that go over multiple lines are tagged with one P tag per line, instead of one P tag per paragraph.

So accessible output support is a bit of a mixed bag right now (only a few tags available, imperfect tagging on export), but it’s at least a good improvement over the prior versions. Here’s the current help page on creating accessible PDFs, and hopefully this is a promising sign of more to come.