2005 Update: In case you’ve come here from a Google search looking for more recent pics, all my shots from the 2005 Solstice Parade can be found right here.

Read on for my original post about the 2004 Solstice Parade…

I got back a while ago from spending the day at the Fremont Solstice Parade and Festival. I had a wonderful time — the weather was incredible, and the parade was a blast. I’m hot, tired, and a bit sunburnt (next time I head out I’ll need to remember to bring the sunblock with me, rather than just putting some on before I leave), but it was very worth it.

The Fremont parade has quite a few things going for it that put it a step above most other parades I’ve been to. Specifically, three things: no corporate sponsorship, no motorized vehicles (human powered contraptions only), and lastly, apparently all it takes to be part of the parade is deciding you want to and showing up with whatever costume, show, or gimmick you want. It’s wonderful.

The Fremont parade has quite a few things going for it that put it a step above most other parades I’ve been to. Specifically, three things: no corporate sponsorship, no motorized vehicles (human powered contraptions only), and lastly, apparently all it takes to be part of the parade is deciding you want to and showing up with whatever costume, show, or gimmick you want. It’s wonderful.

Of course, one of the most notorious aspects of the Fremont Solstice parade is the annual kickoff group of naked cyclists. They were certainly out in full force this year, most wearing nothing more than body paint, and a few eschewing even that minimal level of coloring. The bodypaint work was often incredibly well done, to the point where some of the cyclists looked far more like they were wearing full-body skintight bodysuits than actually naked. Bold splashes of color, racing stripes, flowers, animal prints, or just full-body solid colors abounded.

Of course, one of the most notorious aspects of the Fremont Solstice parade is the annual kickoff group of naked cyclists. They were certainly out in full force this year, most wearing nothing more than body paint, and a few eschewing even that minimal level of coloring. The bodypaint work was often incredibly well done, to the point where some of the cyclists looked far more like they were wearing full-body skintight bodysuits than actually naked. Bold splashes of color, racing stripes, flowers, animal prints, or just full-body solid colors abounded.

Of course, the most amusing side effect of wearing naught but body paint was obvious anytime one of the cyclists stood on the pedals. They’d raise up off their seat, and suddenly you’d get a quick flash of bare skin as the bodypaint stuck to the seat of the bike and left their suddenly unpainted rump standing out in the midst of the rest of the paint.

Members of the Utiliklan were part of the parade, too. A group of seven men in kilts strode down the parade route to the whistles and admiring cheers of the crowds lining the road. Every so often they’d pause for a moment to work the crowd, egging on the cheers and yells, until finally, when they deemed the time was right, they’d line up facing one side of the road or the other, bend down…

Members of the Utiliklan were part of the parade, too. A group of seven men in kilts strode down the parade route to the whistles and admiring cheers of the crowds lining the road. Every so often they’d pause for a moment to work the crowd, egging on the cheers and yells, until finally, when they deemed the time was right, they’d line up facing one side of the road or the other, bend down…

…and with a quick flip of the wrist, they quite handily answered the age-old question of just what a real man wears underneath his kilt.

…and with a quick flip of the wrist, they quite handily answered the age-old question of just what a real man wears underneath his kilt.

Of course, when I got up this morning and saw the weather, I’d donned my kilt for the day’s festivities. Not long after I’d arrived in Fremont I’d shucked off my shirt as well, just wearing a light vest and my kilt. When the Utiliklan made it down to where I was standing, it didn’t take long at all for them to notice me standing there — and the next thing I knew, I had all of them plus a few of the people around me on the sidelines declaring that I was to join them in the street.

I had to do it. Obviously, I couldn’t get any pictures of my impromptu foray into mooning a few hundred total strangers — probably a good thing, too — but given the number of cameras around that day, I may have some ‘splaining to do should any pictures surface during my eventual presidential candidacy! ;)

I had to do it. Obviously, I couldn’t get any pictures of my impromptu foray into mooning a few hundred total strangers — probably a good thing, too — but given the number of cameras around that day, I may have some ‘splaining to do should any pictures surface during my eventual presidential candidacy! ;)

As the parade went on, the revelry, music, and general weirdness continued unabated. A troupe of bellydancers came by, with four dancers preceding them dancing with some long red scarves. Suddenly I realized that one of the first dancers I’d seen before — she’s friends with Don and Chad, and had done a private interpretive dance at last Halloween’s party at Don and Chad’s house. I don’t believe she saw me, and she may not have remembered me even if she did notice me in the crowd, but it was fun to realize that I actually recognized her.

As the parade went on, the revelry, music, and general weirdness continued unabated. A troupe of bellydancers came by, with four dancers preceding them dancing with some long red scarves. Suddenly I realized that one of the first dancers I’d seen before — she’s friends with Don and Chad, and had done a private interpretive dance at last Halloween’s party at Don and Chad’s house. I don’t believe she saw me, and she may not have remembered me even if she did notice me in the crowd, but it was fun to realize that I actually recognized her.

I’m not sure at all what the deal with the dancing bananas was, but there they were, complete with gorilla bounding around from one side of the street to the other. Does there really need to be a coherent reason?

I’m not sure at all what the deal with the dancing bananas was, but there they were, complete with gorilla bounding around from one side of the street to the other. Does there really need to be a coherent reason?

Some of the floats that appear in the parade are just incredible to see. As there are no motorized vehicles allowed in the parade, everything has to be either foot- or pedal-powered, and more than a few contraptions used a combination of the two.

Some of the floats that appear in the parade are just incredible to see. As there are no motorized vehicles allowed in the parade, everything has to be either foot- or pedal-powered, and more than a few contraptions used a combination of the two.

And eventually, after about an hour or so, the parade came to an end. Or, really, the official parade came to an end, as it ended up picking up a huge crowd of former parade watchers tacking themselves on to the end of the line as it proceeded down the street and into Gas Works park. I spent the next couple hours wandering around a good five square blocks (I think, I didn’t explore the entire area) of Fremont had been closed off and turned into a street festival area, then proceeded back down the parade route down to Gas Works Park.

And eventually, after about an hour or so, the parade came to an end. Or, really, the official parade came to an end, as it ended up picking up a huge crowd of former parade watchers tacking themselves on to the end of the line as it proceeded down the street and into Gas Works park. I spent the next couple hours wandering around a good five square blocks (I think, I didn’t explore the entire area) of Fremont had been closed off and turned into a street festival area, then proceeded back down the parade route down to Gas Works Park.

Eventually I decided that I’d had enough sun, and found my way back to a bus route and came back home. Now that I’m showered, slathered down with Aloe lotion, and have tossed this post up, I’m off to grab a nap for a couple hours, as I’ve got a concert to go to tonight: Sister Machine Gun at the Fenix!

The rest of the parade photos are right here (some are NSFW).

iTunes: “Destillat (VNV Nation)” by Das Ich from the album Re_Laborat (2001, 6:08).

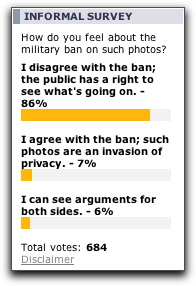

As of just after midnight on Friday morning, with 684 responses, the poll shows an overwhelming 86% of respondents choosing “I disagree with the ban; the public has a right to see what’s going on.”

As of just after midnight on Friday morning, with 684 responses, the poll shows an overwhelming 86% of respondents choosing “I disagree with the ban; the public has a right to see what’s going on.”