I haven’t said anything about this until now, and especially not on Facebook, because I didn’t want to deal with the inevitable flood of “have you tried…” and “you should…” and other such unsolicited advice in the comments (so, please, none of that here either), but:

Damn, COVID is no fun, y’all (and I have relatively mild symptoms).

I’d managed to avoid it until now, even to the point where I was staring to wonder (though not very seriously) if I might be one of the rare few with some amount of natural immunity. Well, that idle fantasy is no more: It was just the right combination of vaccines, boosters, and well-applied caution and masking.

However, when you take a three-week vacation that includes a week on an ocean liner, you accept certain risks. Which we had — though, admittedly, we hadn’t anticipated those risks including a tablemate showing up for dinner obviously ill, sniffling, coughing, bleary eyed, all while assuring everyone that it was “nothing” and “just some bacterial thing” and “not contagious”. In retrospect, we should have excused ourselves immediately, but the combination of wanting to enjoy the fancy dinner and the social pressure of not wanting to look rude (though really, he was the one being rude) meant we stayed and just hoped we’d be lucky enough to escape infection.

We were not lucky.

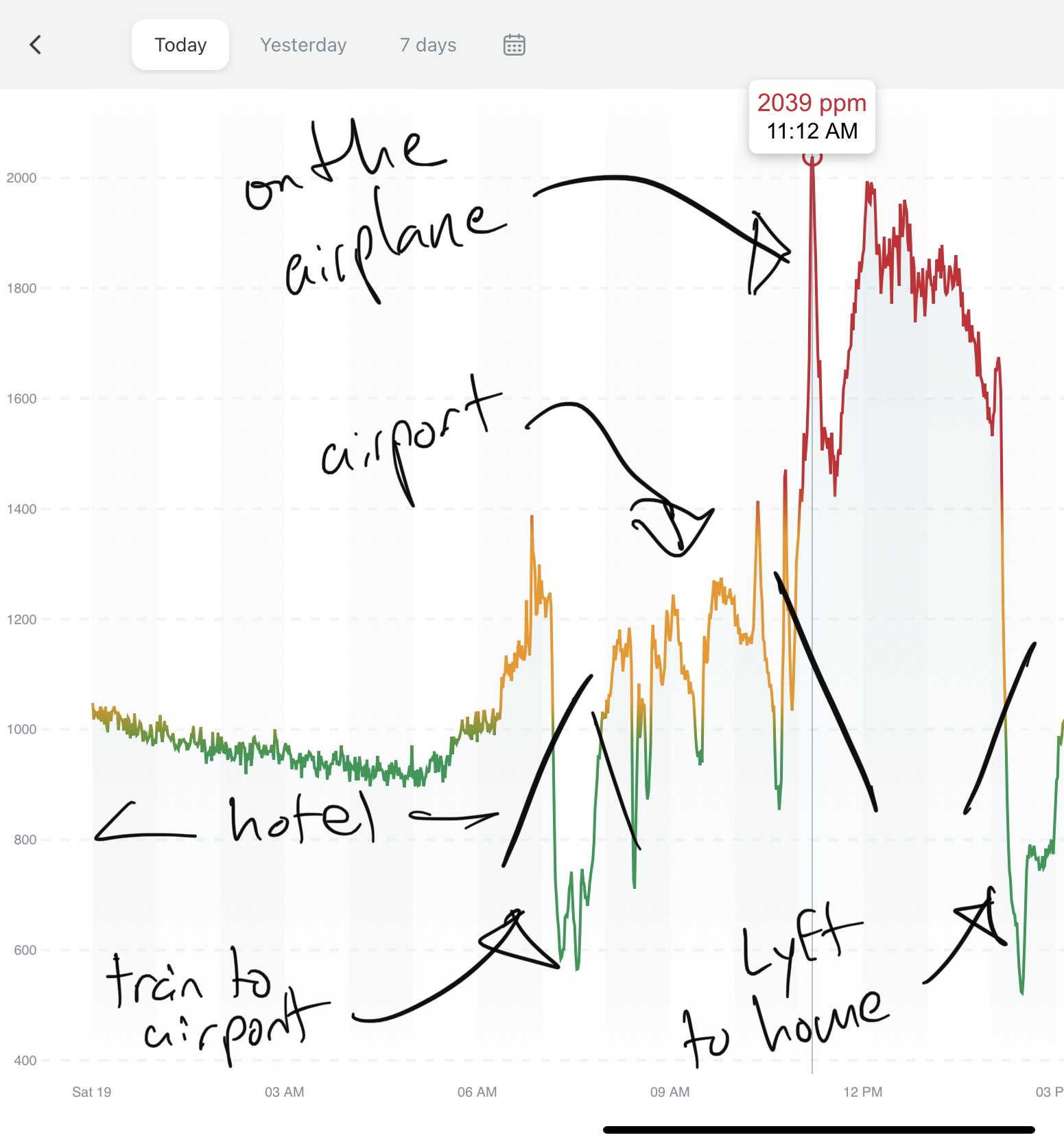

My wife got hit first, a little over halfway through the ocean voyage, and I started feeling it (though much more mild symptoms) a few days later, right towards the end of our stay in London. We COVID tested when she started feeling ill, and it came up negative, so we hoped that it was just a cold, flu, or other some such thing. We spent the rest of our vacation taking things a bit easier, taking cabs around London instead of walking or using buses or the Underground, taking a couple evenings to rest instead of finding more things to do, and of course, masking anytime we were indoors or in crowds (with some brief exceptions for selfies).

But we tested again when we got home, and I pinged positive — a surprise to us both, as my wife continued to test negative even though she had more severe symptoms than I did. But there it was, and with that, we’re just figuring that we managed to test her at exactly the right (wrong) times to miss the peak of detectability.

So, we’ve been isolating at home since we got back from our vacation, and while I’m back at work this week, I’m fortunate enough to have a job where I can just let them know I’ll be working from home instead of coming into the office. This seems to have been a good decision, as my next test 48 hours after the first one also showed positive, though with a much lighter line.

We’re also fortunate that my symptoms have been relatively mild, and my wife’s, while not as mild, still land in the general realm of a bad cold or notable flu rather than anything more serious than that. It’s not fun for either of us, and we’re both getting tired of “sick people food” (there has been a lot of soup since we got back home), but at least we have the ability to stay at home, take care of ourselves, and avoid risking anyone else. And hopefully, we’ll be through the worst of this in another few days.

But for now? We’re grumpy, and incredibly annoyed at our tablemate on the ship. Though we’ll never know for sure, and the source could have been someone else (we were virtually the only people we saw on the ship wearing masks at any point), he’s such an obvious likely vector that he has definitely been receiving the brunt of our ire.

Such a pity that people suck so much. I was really enjoying my “no COVID so far” status. No more of that for me, though.