With all the recent news concerning the NSA’s surveillance programs (Prism et al.), one of the common defenses has been that for at least some of these programs (though not all), the government is “just” collecting metadata. For example, should the government access your email records, they might not have access to the content of the email, merely the associated data — like who you communicate with, when, how often, who else is included in the messages, and so on.

Techdirt has a good overview of why the “it’s just metadata” argument is a foolish argument to make — basically, there is a lot of information that can be derived from “just metadata” — but there’s also an MIT project called “Immersion” (noted in the TechDirt article, though I found it elsewhere) that gives a good visualization of what can be learned from a relatively limited dataset.

Immersion scans your Gmail account (with your explicit permission, of course), and then runs an analysis on the metadata — not the content — of your email history to create a diagram showing you you communicate with and the connections among them.

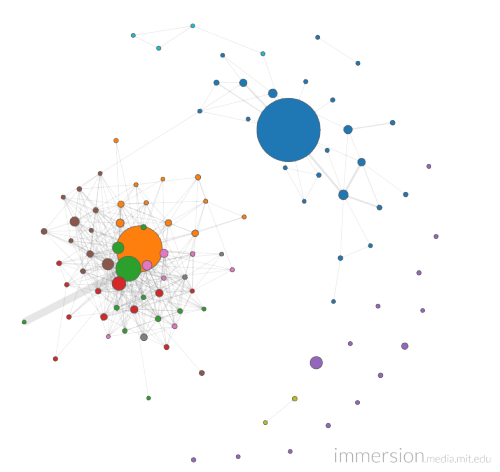

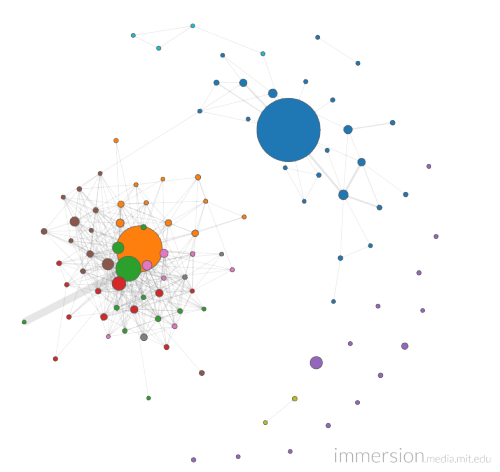

As an example, here’s my result (with names removed). This is an analysis of almost 52 thousand messages over nearly nine years among 201 separate contacts. Each dot is a single contact, the size of the dot is a measure of how often I’ve communicated with them, and the lines between them show existing relationships between those people (based on messages with multiple recipients).

In that image, there are two obvious constellations: the blue grouping at the top right are my family and long-time friends; the orange/green/red/brown grouping to the left are my Norwescon contacts. The scattering of purples and yellows are contacts that fall outside of those two primary groups. While there’s not much here of great surprise or import for me, I did already learn one thing of interest — apparently one of my old high school friends has had some amount of contact with one of my Norwescon friends (that’s the single line connecting the two constellations). Now, I have no idea what sort of relationship exists between them — it could be nothing more than my sending a group email that included one and accidentally including the other as part of the group — but some sort of relationship does, and that’s information I didn’t have before.

Now, my metadata is fairly innocuous. But for argument’s sake, suppose I was involved not with Norwescon, but with some other group of people that, for whatever reason, I wanted to keep quiet about. Maybe I’m involved in the local kink scene, and could face repercussions at my job or in my personal life if this became known. Maybe I’m having a gender identity crisis that I’m not comfortable publicly discussing, but have a strong internet-based support group. Maybe I’m part of Anonymous or some similar group, discussing ways to cause mischief. Maybe I’m a whistleblower, and these are my contacts. Maybe I’m a news reporter who has guaranteed anonymity for my sources — but suddenly, this metadata exposes not only who I communicate with, but when and how often, and if there’s a sudden ramp in communication between me and certain contacts in the weeks or months before I break a big story with a lot of anonymous sources, suddenly they’re not so anonymous any more. And, yes, of course, because no list like this would be complete without the modern boogeyman that is the government’s excuse for why this surveillance is necessary — maybe I’m a terrorist. (For the record, I’m none of the above-mentioned things.)

However, of that list of possibilities, terrorism (or, less broadly, investigation of known or suspected crimes) is the only one that the government should really have any interest in, and that’s exactly the kind of investigation that they should be getting warrants for. If they suspect someone, get a warrant, analyze their data, and build a case from there. But analyzing everyone’s data, all the time, without specific need, without specific justification, and without warrants? And then holding on to the data indefinitely, allowing them to troll through it at any time for any reason, whether or not a crime is suspected?

There’s a very good reason why terms like “Orwellian”, “Big Brother”, and “1984” keep coming up in these conversations.